There is a kind of bias in most modern fiction that favors writing which seeks to make itself invisible, that the language itself shouldn't "get in the way" of the story, that the story is all-supreme, like a thought buried in a slab of marble that only require the writer to carefully carve it out. This is a tendency toward realism, or at least toward a certain kind of realism, which stands in opposition to the poetic, language for the sake of language, the ornamental or self-conscious, language that stands out. That the writer is best advised to write himself out of the writing, as it were, and not let his "ego" interfere.

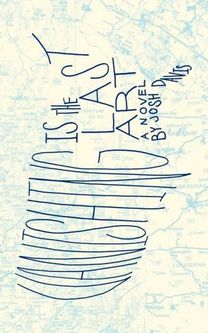

This notion seems to coincide with the title of Josh Davis’s latest novel "Vanishing is the Last Art" (Pretend Genius Press), but in terms of language, this is not a novel of disappearing, but of an almost obsessive appearing, of over-appearing. The language drives the story along, the story (if now it is a story? The appearing) of Charlie Fell, a somewhat indifferent but ironically enthusiastic seller of baseball cards (or whatever it is), traveler of external and internal landscapes, romancer of women and moments.

The novel is told in loosely fitted scenes, fragments, rants, parties, that along with the poetic language gives an overall detached feeling, like a thin film of something draped over everything, which is not a bad thing, hinting of this disappearing. The feeling is that you just can't quite be sure about the "reality" of what's going on. We are firmly in Charlie Fell's head and Charlie Fell is that kind of narrator who might be truthful, but then again might not. He’s both there and not there, likable and not likable. He might be a walking ghost stuck in purgatory collecting not baseball cards but lost souls.

But back to the writing, the language, which, on practically every page, bursts with tongue-twisting, remarkable poetry. Sometimes, and that is my only complaint, the enthusiasm and jokes and clever observations become slightly too nerdy and, at least for me, at times, fall flat. This is two sides of the same coin, and will probably turn some people off, at least those who like to carve marble: an almost carnal energy and love for the written word (permit me to quote one of many delightfully punch-drunk, blistering paragraphs):

"I am starting to miss rudeness, slanted eyebrows, the ability to shock, pizza that doesn’t taste like leather, and the lullish orchestra of car horns that follows a single offender for days—that draws large red A’s on car hoods, and incites finger parades as far as the eye can see. I miss the sleazy pick-up artist, the academy award performance of barflowers, and the sweet choking aroma of sixteen kinds of smoke blending into the ineffable potpourri of the east. I miss orange alerts meaning something. I can’t believe I just said that, but I do. I miss the toothless, trailer huddled masses. I miss jukeboxes with filthy, vulgar bar-rock. I miss the fear, the stiffness, the pallor, and the knowledge that at least half the other poor bastards in any given room at any given time will be going home tonight with their right hand. I miss grit and impropriety. California, you make me want to wash my hair in tar, have my teeth painted at a Chinese beauty parlor, and don a proper Brooklyn boom box blasting the fuck out of Public Enemy records against the sweat stream out of the suited, untranquilized masses—thinning hair, semen stains, sullen shoes, deranged eyes, madness—hungry madness—beautifully damned, and archetypally bemused death vultures that hang over us all that we call man, women, husband, wife, sir, madam, doctor, dealer, boss, paperboy, clerk, whore, bastard, junkie, or Mr. President."

There is an obvious influence in Davis's writing of that kind of beatnicky stream of consciousness, but it seems whenever you make that comparison, you can't help but to simultaneously cover the work with an inescapable perfume of dead urine and nostalgia. Vanishing is the Last Art (or VITLA, as the kids are calling it) luckily escapes this awkward decomposition: it doesn’t reek of sentiment for a better time in the past but pushes relentlessly against the (more dull, perhaps, harder to find a grip) edges of our current society, but also against the edges of what is meant by adulthood (Charlie Fell seems to be stuck in this kind of prolonged defiant pubescent limbo), and ultimately the sticky super-edge business of what makes a person (am I real?)

Actually, reading VITLA, and it’s the first time I'm reading anything by Josh Davis, I was reminded more of Chuck Palahniuk than Jack Kerouac, in the furious drive of the prose which feels more like poetry, the rhythm and repetition, the imagery, the schemes, characters drunk on modern romantic loser's detachment syndrome. Where Palahniuk's sordid wit is incomparable, Davis has a particular knack for describing people and their seductions (I always hated Palahniuk's sex scenes, he suddenly turns into a metaphor cheese shop.)

Anyway. I enjoyed this book and recommend it to anyone who likes books that seethe with the whole spectrum of human emotions, shamelessly, and refuse to go to rehab.

-Kim

see www.vanishingisthelastart.com/ for more details.

This notion seems to coincide with the title of Josh Davis’s latest novel "Vanishing is the Last Art" (Pretend Genius Press), but in terms of language, this is not a novel of disappearing, but of an almost obsessive appearing, of over-appearing. The language drives the story along, the story (if now it is a story? The appearing) of Charlie Fell, a somewhat indifferent but ironically enthusiastic seller of baseball cards (or whatever it is), traveler of external and internal landscapes, romancer of women and moments.

The novel is told in loosely fitted scenes, fragments, rants, parties, that along with the poetic language gives an overall detached feeling, like a thin film of something draped over everything, which is not a bad thing, hinting of this disappearing. The feeling is that you just can't quite be sure about the "reality" of what's going on. We are firmly in Charlie Fell's head and Charlie Fell is that kind of narrator who might be truthful, but then again might not. He’s both there and not there, likable and not likable. He might be a walking ghost stuck in purgatory collecting not baseball cards but lost souls.

But back to the writing, the language, which, on practically every page, bursts with tongue-twisting, remarkable poetry. Sometimes, and that is my only complaint, the enthusiasm and jokes and clever observations become slightly too nerdy and, at least for me, at times, fall flat. This is two sides of the same coin, and will probably turn some people off, at least those who like to carve marble: an almost carnal energy and love for the written word (permit me to quote one of many delightfully punch-drunk, blistering paragraphs):

"I am starting to miss rudeness, slanted eyebrows, the ability to shock, pizza that doesn’t taste like leather, and the lullish orchestra of car horns that follows a single offender for days—that draws large red A’s on car hoods, and incites finger parades as far as the eye can see. I miss the sleazy pick-up artist, the academy award performance of barflowers, and the sweet choking aroma of sixteen kinds of smoke blending into the ineffable potpourri of the east. I miss orange alerts meaning something. I can’t believe I just said that, but I do. I miss the toothless, trailer huddled masses. I miss jukeboxes with filthy, vulgar bar-rock. I miss the fear, the stiffness, the pallor, and the knowledge that at least half the other poor bastards in any given room at any given time will be going home tonight with their right hand. I miss grit and impropriety. California, you make me want to wash my hair in tar, have my teeth painted at a Chinese beauty parlor, and don a proper Brooklyn boom box blasting the fuck out of Public Enemy records against the sweat stream out of the suited, untranquilized masses—thinning hair, semen stains, sullen shoes, deranged eyes, madness—hungry madness—beautifully damned, and archetypally bemused death vultures that hang over us all that we call man, women, husband, wife, sir, madam, doctor, dealer, boss, paperboy, clerk, whore, bastard, junkie, or Mr. President."

There is an obvious influence in Davis's writing of that kind of beatnicky stream of consciousness, but it seems whenever you make that comparison, you can't help but to simultaneously cover the work with an inescapable perfume of dead urine and nostalgia. Vanishing is the Last Art (or VITLA, as the kids are calling it) luckily escapes this awkward decomposition: it doesn’t reek of sentiment for a better time in the past but pushes relentlessly against the (more dull, perhaps, harder to find a grip) edges of our current society, but also against the edges of what is meant by adulthood (Charlie Fell seems to be stuck in this kind of prolonged defiant pubescent limbo), and ultimately the sticky super-edge business of what makes a person (am I real?)

Actually, reading VITLA, and it’s the first time I'm reading anything by Josh Davis, I was reminded more of Chuck Palahniuk than Jack Kerouac, in the furious drive of the prose which feels more like poetry, the rhythm and repetition, the imagery, the schemes, characters drunk on modern romantic loser's detachment syndrome. Where Palahniuk's sordid wit is incomparable, Davis has a particular knack for describing people and their seductions (I always hated Palahniuk's sex scenes, he suddenly turns into a metaphor cheese shop.)

Anyway. I enjoyed this book and recommend it to anyone who likes books that seethe with the whole spectrum of human emotions, shamelessly, and refuse to go to rehab.

-Kim

see www.vanishingisthelastart.com/ for more details.