the dictionary of coincidences volume 1 (hi) is Sean Brijbasi’s fourth (that we know) collection of letters/words/things (forthcoming on (publishing press unknown)), following Still Life in Motion (2004), One Note Symphonies (reissued 2007), The Unknowed Things (2009) (all available through pretend genius press), and his first attempt at an actual dictionary. This is not a bad fit. It is successful in that it too has words arranged alphabetically.

Note: Some of these words appear to have been translated from a foreign language. Some of these words appear to be in a foreign language.

Comparative analysis:

Dictionaries have given rise to many heated debates, not just among scrabble enthusiasts, but perhaps most notably between descriptives (so called “caps”) and prescriptives (so called “hats”), the two major parties in the dictionary world, where the former seek to describe words as they are (“come on baby, nice and slow/ride like you in the rodeo”) and the latter words as they should be (“To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds”). Many (letter) heads have rolled (ha). Ain’t to be resolved anytime soon, irregardless.

What continually seems to inform Brijbasi’s writing is this tension between form and matter, language as containment and language as wild-eyed irreverent party girl. Language that says Yes Sir and language that says Woohoo Bob and language that says Yeah Well? Fuck You Too. The dictionary, as a form, perhaps the most ancient and complete of the many literary forms, provides here a sexy straight-jacket in which we get to witness the 'poet' dislocate himself. Our eyes wander to Houdini’s Milk Can Escape of 1901 and it’s unmistakable influence on Freud’s Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten (on joking with the unconscious) four long years later.

A possible signifier of this writing “style”, if we must signify, if we must speak of styles (we must speak of isms), is an experiment which seems to draw more from modernism than post-modernism, a kind of new- or new-new-romanticism which amplifies rather than subdues the “poetic”, wiggling loose the aching tooth of “after” and rarely stray, however weird-ass, from the possibilities of narration. Even in the weird-assest and most abrupt sections of the dictionary of coincidences volume 1 (hi) we sense the narrator hiding, possibly behind a curtain, like that old man what's-his-name in Hamlet, and it is in this space between the weird-ass and the narrator (the question of the narrator/the question of the weird-ass) that the text seems to come alive.

This “come alive” will probably not happen if you have spent too much time riding around town on the bicycle known as realism and need to get your fix of plot and character development, forwardness and what not. Then you will probably read the first word of A ("ableberry") and speak of such things as pointless cleverness nonsense pretentious artsy bullcrap for the sake of pointless cleverness nonsense artsy bullcrap pretentious. This is a popular multi-edged response to art, that at the same time it is too much (artsy), that it is useless (for the sake of itself), too little (bullcrap), fake (pretentious) etc., or in other words: “my child could do that!” A popular response to such a response is to defend art, to educate art, to guard art, to call forth art’s meaningfulness, art’s rareness and fine fine goody good-ness. This is a mistake. Art is dumb and pointless and too much and too little (contradictions) and yes, useless, and yes, your child could do it. Is doing it right now in fact. While you’re reading this your child is drawing bold circles with a red magic marker all over your functional cabinets.

dreams of terrible angels

two lovers in the snow. Two lovers framed by jade (color). Two lovers pierced by the sword of a mighty rhododendron (flower).

Ros|e-mary (heaven). The gentles call to you from Hibiscus. The bare settles in. The cardinal falls through the ice—his mitre a maypole for more graceful children, who having filled their cheer with scrawn, live artfully among the mundane.

Stricken with night, the dog breaks its own leg and vomits the stars before us.

I can’t remember the songs. Only the women who sang them and the ground they stood on. The bluster of hair as clouds moved behind them. Praying to the old logic. We who are human never wanted the necessity. The looking up in shock. The inevitable coming to this of life. When she died I followed her to the door and held her face in my wound. They say there will be more for those who are beautiful.

-from the dictionary of coincidences volume 1 (hi), under D

...

At once we notice that to seek a penetration of such a work will surely prove foolhardy (as penetration is suggestive of depths). How then shall the work be addressed, properly read? I mostly read it laying down with my feet slightly elevated recuperating from a terrible swelling (and painful) caterpillar infection. I would propose thus that one good way of reading the dictionary of coincidences volume 1 (hi) is to read it improperly, to read it like one might hold eye-contact with a stranger beyond the appropriate micro-moment and into the creepy and awkward after-moment, to read it dumbly (and dimly) and let the infection of language take hold, set you temporarily into a raging fever.

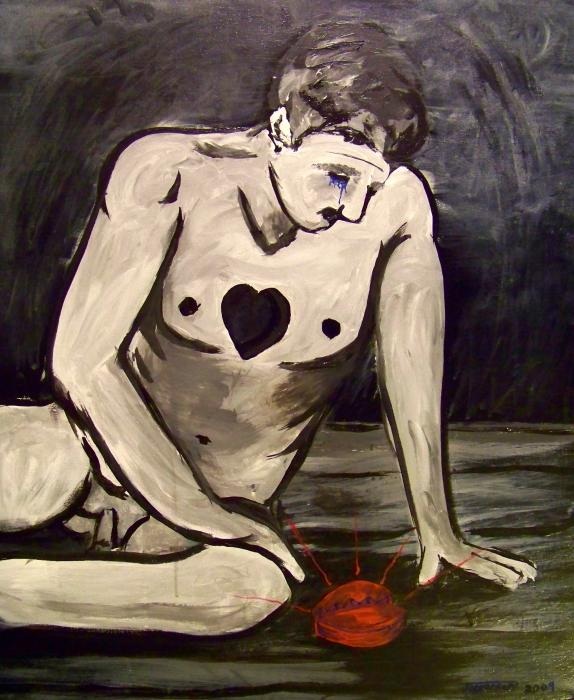

It might also be helpful to consider the work as a pose. In the introduction to the work Sir De(s)mon-d Mott writes: “There is little if anything profound about ‘the dictionary of coincidences, volume i (hi)’. It is only appearance.” A pose (in its dumb undepthness) is often infectious without aspiring internal-mushy-ness: I touch my nose you touch your nose I touch your nose. (In fact, the mushiness, the sentimental, in Brijbasi's multiverse, is often pushed past its own expiration date, that it accomplishes an air of the post-sentimental). Esteemed feminist, children's book writer and psychoanalyst Rita Hubbert writes: “A pose is a question that can only sufficiently be answered with a counter-pose. Consider the caged monkey flaunting his swollen buttocks to passing-by tourists in some zoo. We can say that such a pose is nonsensical, a provocation, a boldness, a gesture, an embarrassment, a random act of monkey violence that exist only to egg our irritation. Which is to say, we choose to emphasize the monkey’s monkeyness, as in “you fucking monkey”, you-them-monkey vs. me-us-not-monkey, for to entertain the possible honesty of such an act, such a pose, such an art, to take such a question seriously […] threaten surrender and acknowledgment of a similar bare obviousness, a similar aching sullen assness in ourselves. Indeed, it threatens to upend all our carefully constructed identities, civilities (virility) and hierarchies.” (Long Last The Horizon, unlearn matter, 2004)

Experimental novelist No Jung Cho writes in his IShitAmerica (Innit, 2009): “To pose is to be empty and defecatingly alone, open to shattering rejection.”

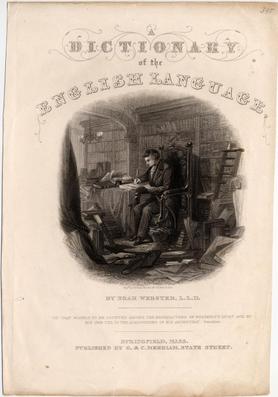

Yes. Reading Brijbasi, we are reminded of this monkey shit, this almost-human, this too-human, this troubling posing and prancing assness in ourselves. If the monkey could typewrite, we find ourselves asking, how wondrous and inspired would not his mating song be, how informed and anguished his love letters? Would he not, like so many before him (Goethe, Bartok, Bell), plagued with too much disorienting longing, explode the very confines of his expression? Noah Webster, who spent twenty-seven years collecting seventy thousand words for his dictionary, learning twenty-six languages (lies), only to die an unspectacular death from old age, was he not also in hot pursuit of love and that which we might call "the flighty", or at least a compatible mate? In his entry on love from 1828 we find the puzzling “9. A thin silk stuff. Obs.” On being broken-hearted he writes: “Having the spirits depressed or crushed by grief or despair.”

Please ask yourself the following questions ahead of our reading group discussion next Friday.

- A kind of unlearning of proper language connection?

- Means a kind of infancy of language?

- Words without context and context without words?

- What is a word?

- A kind of painting with words (and in words)?

- Splash splosh plosh.

- Once we were happy.

- Where is the “trauma”?

Above all, the dictionary of coincidences volume 1 (hi), like all half-decent poetry, is a love letter. It is also a traveling log, a shipwreck, and a welcomed anti-venom to the tyranny of reason. As American short-story-flash-ness it stems not, as so much such, from mute Hemingwayan macho-realism ("On the table stood one solitary flower-pot. Die, motherfucker, die.") but have one foot hanging aloof in the Eurovision tradition of the fleeting (and flamboyant) inward.

This has been an introduction to the dictionary of coincidences volume 1 (hi) by Sean Brijbasi. If you possess a kindle and are some kind of member and wish to quickly aquavit yourself with Sean’s writing, The Unknowed Things is available for (I think, more or less) FREE on amazon. Stay attuned to developments regarding the release of the dictionary of coincidences volume i (hi) at: www.seanbrijbasi.com.

Or www.pretendgenius.com

Or watch this trailer for tDoCv1 (hi).

Next week we will take a closer look at the dictionary's main characters and "How The Dictionary Gave Me The Evil To Sit Down In The Face Of Great Courage"

-Juniper D'artagnan